Essays

Long-form rants, explorations, flights of fancy.

-

“No notes are given as I can’t remember all of the sources.”

-

Göteborg Book Fair 2019 provided an opportunity to re-immerse myself in Korean literature and culture via a mini-festival of humanity.

-

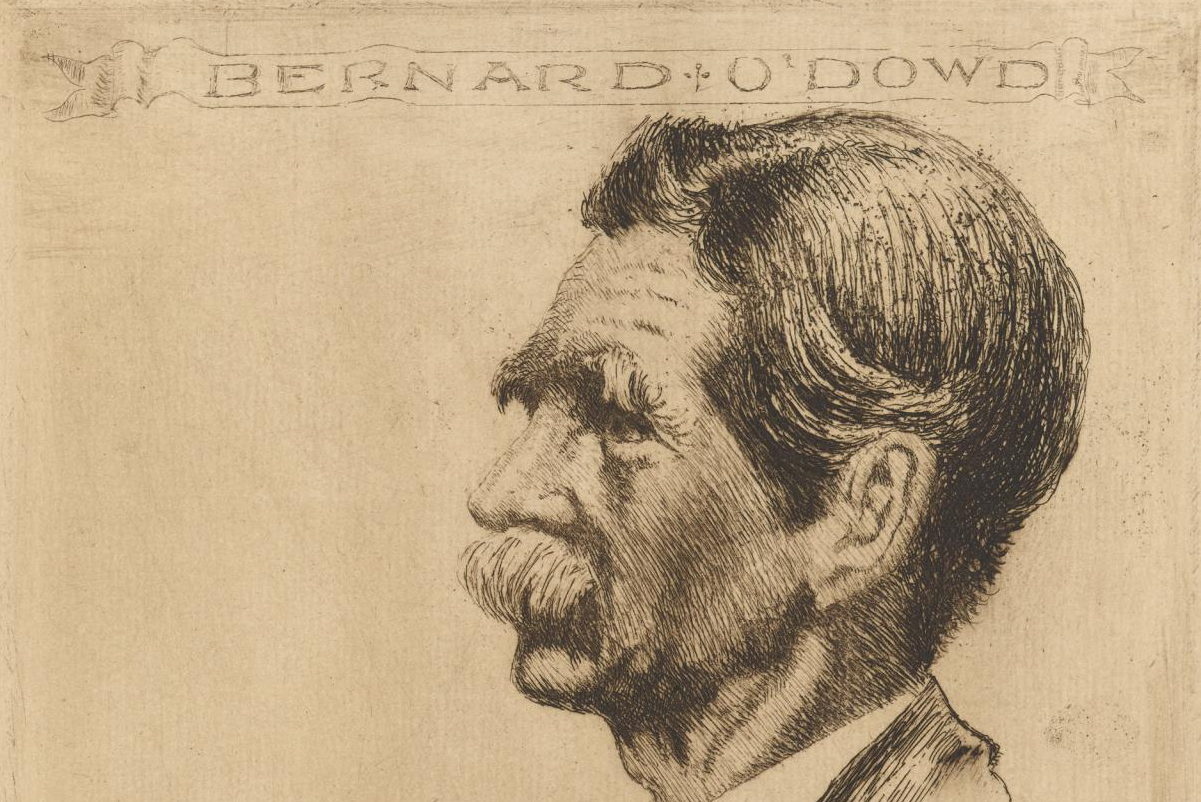

What happens when you cross a rhyming sonnet (written on the eve of the federation of Australia) with a 21st-century, post-avant sensibility?

-

We need to talk about Chris de Burgh’s lyrics.

-

After taking an eternity to write my review of Animal Collective live in concert, I’ve decided to turn over a new leaf and get snappy. So, without further ado, some words and pictures from last week’s Kraftwerk gig at Cirkus in Stockholm.

-

Documenting my Animal Collective journey, from 2008 to 2012.

-

Poem Communities

•

3 min read

Growing up in the 1980s in rural Australia, I immersed myself in two passions: reading books and playing sport. I was never much one for football or cricket, preferring instead cross-country running, endless laps of the pool and, perhaps most vitally, tennis.

![[d/dn]](https://i0.wp.com/daveydreamnation.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/oie_l521ir34eJuC.png?fit=136%2C116&ssl=1)