I’ve been flat out digging through the online archives of the Chris de Burgh website, in particular the vast wealth of information contained within the Man On the Line (MotL) section, wherein Chris personally responds to questions and queries.

While, unfortunately, the MoTL section has now been deleted from the website, thanks to the wonderful Internet Archive we’re able to continue to access the sheer beauty of CdeB interacting with his fans. One such fan asked:

. . . any chance you’d release some of those haunting lyrics as a book of poetry? They read just as well as they’re sung. Hold that thought! I want 10% of the royalties!!!

—Joseph Cotter from Cork, Ireland, 25 April 2007

Chris’ response was interesting for its glancing reference to the poetic craft:

I am not sure that song writing lyrics when written on a page are as anywhere near as good as when they are accompanied by a melody. Because that’s what they are designed for. And they might look a bit banal or indeed dull if not accompanied by the music that they have been set to.

—Chris de Burgh, 25 April 2007

While it has always been my determination to demonstrate that the lyrical output of de Burgh in the 1970s and early 1980s was nothing short of prodigious, and amounts to a cultural phenomena, I am sure even the casual fan of Chris would agree that even in these ‘Norman-era’ years Chris has his moments, and then he has other moments which he will later regret.

And these regrets compound upon one another, here, at the end of his apprenticeship as a poet, from which he will emerge, but two years later, as the first of his great historical guises: that of the Crusader. Onwards …

Indeed, we may safely classify much of CdeB’s lyrical output post-Man On The Line as both ‘banal’ and ‘dull’ but be that as it may, what we get on At the End of a Perfect Day, is not, as many expected, de Burgh’s difficult third selection of melodiously-crafted odes and plaints—rather, it constitutes a brash statement of intent.

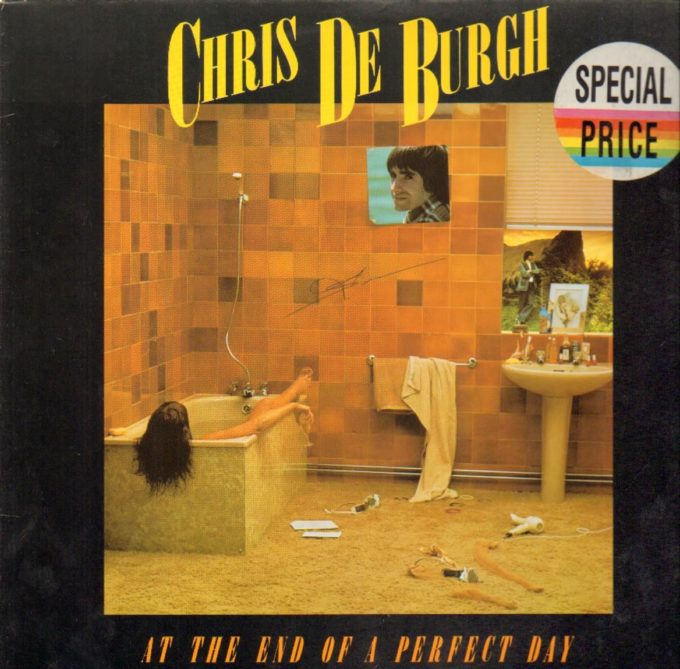

The cover image for the album was, as with Chris’ later album cover artwork (I speak, naturally of the brutally honest and revealing photograph used for The Crusader album cover), self-obsessive. Of which more later, of course. But for now, read this with me, in Chris’ own words, a response to Lance Johnson (37) from Arizona, USA:

The lady in the cover of At The End Of A Perfect Day was a hired model. I wasn’t at the photo shoot. I did all the other ones of course. And as you may remember she is lying in a bath staring up at a picture of me. When I look at that cover, I think it is a little bit corny and different and a bit strange. I think it could have probably been better under the circumstances. But when you are struggling for ideas to represent a title like ‘At The End Of A Perfect Day, isn’t it a nice idea to be luxuriating in a nice hot bath and staring at a picture of somebody you admire or love. And that’s what we came up with.

Chris de Burgh, 9 April 2007

Is it any surprise then that the poems contained within this ‘slim’ volume range not so much between as within the genre of Norman-era invasion movie megalomania and a kind of weird post-industrial balladeering rendered utterly irrelevant by the events around it that is somehow, strangely, impervious to change, even to itself?

Opening poem ‘Broken Wings’ sets the scene gracefully enough, from the point of view of a migratory bird (perhaps, a seagull):

These broken wings can take me no further,

I’m lost, and out at sea,

I thought these wings would hold me forever,

And on to eternity . . .Chris de Burgh, ‘Broken Wings’

But on and on it goes in second poem, ‘Round And Around’, a laborious effort at best, riddled with ellipsis:

Oh around and around . . .

Everything in the world goes around,

Oh around and around . . .

Everything goes around,

Yes around and around . . .

Oh around and around . . .

Everything in the world goes around . . .Round and around, round and around, round and around . . .

Chris de Burgh, ‘Round and Around’

Things take a turn for the better on ‘I Will’, an up-tempo ‘island’ number, which sets the scene perfectly for ‘Summer Rain’, a promisingly-titled and yet strangely discordant poem, set as it is amongst the sentimental blarney of old men, children on knees and other blather:

Ah la la la, summer rain is pouring down again,

And it’s getting wetter,

As a matter of fact it couldn’t be better . . .Chris de Burgh, ‘Summer Rain’

Astute readers will have noticed, of course, correspondences between the use of ‘la la la’ here, a device used also by Belinda Carlisle, not in her song ‘Summer Rain’ but in the title of the song ‘La Luna’. Whereas the superb middle verses of ‘Summer Rain’, if you will recall, absolutely nail it:

I remember the rain pouring down

And we poured our hearts out

As the train pulled out

I can see my baby

Waving from the train

It was last time that I saw him

In the summer rainEvery time I see the lightning

Every time I hear the thunder

Every time I close the window

When this happens in the summer

Oh the night is so inviting

I can feel that you are so close

I can feel you when the wind blows

Blows right through my heartBelinda Carlisle, ‘Summer Rain’

Clearly, de Burgh’s ‘Summer Rain’ is no match at all for Carlisle’s warbling delivery here. And yet . . . and yet.

Rounding out the first half of this collection of lyrics is a ditty called ‘Discovery’, which seems to be about some kind of sailor (another of de Burgh’s recurrent dis-guises) who has discovered something. But what, exactly?

One day says Galileo,

A man will reach the sky,

And see the world completely,

From outside,

And gazing down from younder,

On a world of blue and green,

He’ll say with eyes of wonder,

I have seen, I have seen,

My eyes have seen.

I have seen,

My eyes have seen.Chris de Burgh, ‘Discovery’

In the end, it turns out that what Chris has discovered is his lighter side.

It’s only fitting that the second set of poems in this collection should begin with the barmy, and yet kind of magnificent, ‘Brazil’. As a precursor to the hedonism critiqued on the Eastern Wind album (see ‘Record Company Bash’, among others), Chris employs the voice of a party-mad Norman-era raver let loose in Rio, amongst other places in

Ah la la Brazil,

Ah la la Brazil,

Ah la la Brazil,

Ah la la Brazil,Chris de Burgh, ‘Brazil’

and so on. Actually, it gets worse before it ends completely:

Ooh, Rio de Janeiro is the kind of place for me,

Dancing in the moonlight, making love down by the sea,

From Copacabana to the Corcovado hill,

Everybody’s always singing in Brazil,

Yeah, everybody’s, ooh singing, in Brazil,

All together now . . .Ah la la Brazil . . .

Cancao du Brazil . . .

(Song of Brazil)

Tudo beum Brazil . . .

(All’s well in Brazil)

Ah la la Brazil . . .Chris de Burgh, ‘Brazil’

Shall we move on?

Perhaps the placement of ‘Brazil’ at the beginning of the second set of poems could be viewed (retrospectively) as a minor mistake, given that it is immediately followed by one of de Burgh’s finest pre-Getaway lyrics. I am speaking, plainly, of ‘In a Country Churchyard (Let Your Love Shine On)’. I would just like to let the lyrics of this song do the talking for a moment:

In a country churchyard there’s a preacher with his people

Gathered all around to join a man and woman,

Spring is here and turtle doves are singing from the steeple,

Bees are in the flowers, growing in the graveyard,

And over the hill, where the river meets the mill,

A lovely girl is coming down

To give her hand upon her wedding day.Chris de Burgh, ‘In a Country Churchyard (Let Your Love Shine On)’

This will be seen by many, in retrospect, as one of the finest late-Romantic Norman-era invasion film lyrics ever written by de Burgh, in which he re-discovers his pastoral self. Far from the sensual, almost seductive self-centredness of the album’s cover art (the perfection of a woman’s adoration of her ‘man’), this poem is in fact two poems, written in interlocking stanzas.

The other poem (the one referred to in the ‘Let Your Love Shine On’ section of the title) is, in comparison with this idyllic rural religiosity, a kind of big brass band coming through the poem, completely unnecessary and annoying to read:

Let your love shine on

For we are the stars in the sky,

Let your love shine strong

Until the day you fly . . .

Let your love shine on

For we are the stars in the sky,

Let your love shine strong

Until the day you fly . . .

Fly away . . .Chris de Burgh, ‘In a Country Churchyard (Let Your Love Shine On)’

I get the idea of the bird as the artist on a wing, I so get it. I also get the sanctity of whatever it is de Burgh is trying to express here. It’s just that I’m left wondering why I should care.

This leaves a rather large question mark hanging over the whole construct of the collection. ‘A Rainy Night In Paris’ is exactly what its title suggests; but in ‘If You Really Love Her, Let Her Go’ de Burgh expresses a more complex emotion, and we feel a little closer to the narrator, this unapproachable genius saboteur balladeer from the 1920s caught up in custody battles and relationships between parents and children, returning once more to the wandering seagull, this time, a daughter:

Oh she is like a bird,

Yearning for the winter wind,

If you let her go,

She’ll come again in springtime,

But if you make her stay,

And hold her freedom in your hand,

In the morning you will wake,

And she’ll be gone away . . .Chris de Burgh, ‘If You Really Love Her, Let Her Go’

Finally, on ‘Perfect Day’, we get another glimpse in to the private world of de Burgh. It is the world of a man who, just like any other man or woman for that matter needs musical stimulation.

He is a man who evidently suffers, like his contemporary Rod Stewart, from the sporadic desire to engage in bar-room singalongs in tuxedos after staggering losses on the blackjack table in some casino in Dubai kind of feeling. Of course, the bardic and Orphic traditions go back a long way in Chris’ family and culture. We should not be surprised by its presence here.

But the glimpse of the Inner de Burgh offered here is one far more in keeping with the album’s cover and title than the rest of the poems preceding it. Here we see de Burgh utterly disarmed, relaxed and, above all, in fine and melodious singing form, celebrating his peculiar version of Lou Reed’s ‘Perfect Day’:

Packed up a picnic and set off for the sea,

Taking all the back roads where no-one else would be,

Me and you and Paul and Sue,

How we laughed the time away,

And we had a perfect day.I brought along my old guitar,

And lying there beneath the stars,

We sang all the Beatles songs we knew,

Lord you should have heard those harmonies,

When we did ‘Nowhere Man’ and ‘Let It Be’ . . .Chris de Burgh, ‘Perfect Day’

We who were not witnesses to this are left with the impression that the true meaning of this collection’s title is in its expression of that moment when one realises that the poem is over. Or does this mean that the end of a perfect day occurs at hat moment when one realises that At the End of A Perfect Day is over?

Perhaps we shall never really need to know.

![[d/dn]](https://i0.wp.com/daveydreamnation.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/oie_l521ir34eJuC.png?fit=136%2C116&ssl=1)

Reply