Tag: australia

-

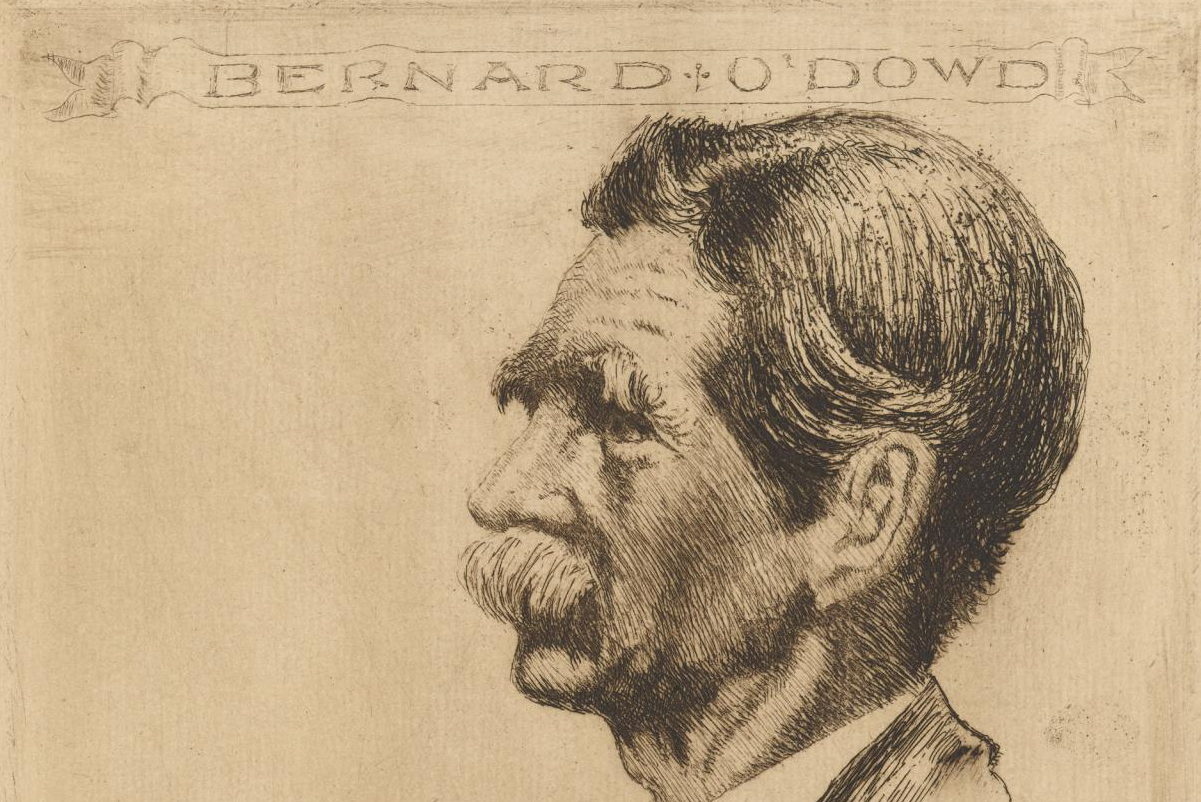

What happens when you cross a rhyming sonnet (written on the eve of the federation of Australia) with a 21st-century, post-avant sensibility?

-

16 reasons why I will find it hard to go ‘home’ in January 2014.

-

One of the billions of reasons why I always find it hard to go ‘home’ to Sweden.

-

Just a little Youtube number in honour of Invasion Day (previously known as Australia Day).

-

Jag är glad över att vara tillbaka i [Sverige]. Ett land som jag länge beundrat, och där min karriär som diplomat började för nästan trettio år sedan. Australien och Sverige har en lång gemensam historia. Faktum är att Australien kude ha blivit svenskt. Gustav den tredje gav order om en svensk bosättning i Västra Australien…

![[d/dn]](https://i0.wp.com/daveydreamnation.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/oie_l521ir34eJuC.png?fit=136%2C116&ssl=1)